Act 3: Web scraping¶

Now that we’ve covered all the fundamentals, it’s time to get to work and write a web scraper.

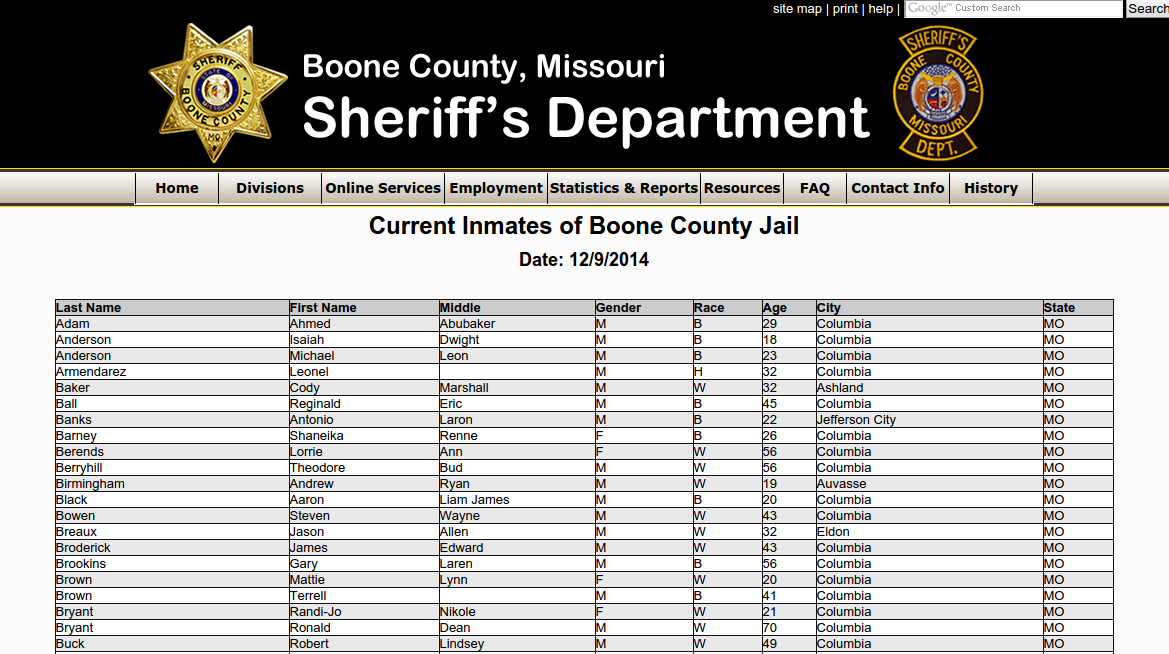

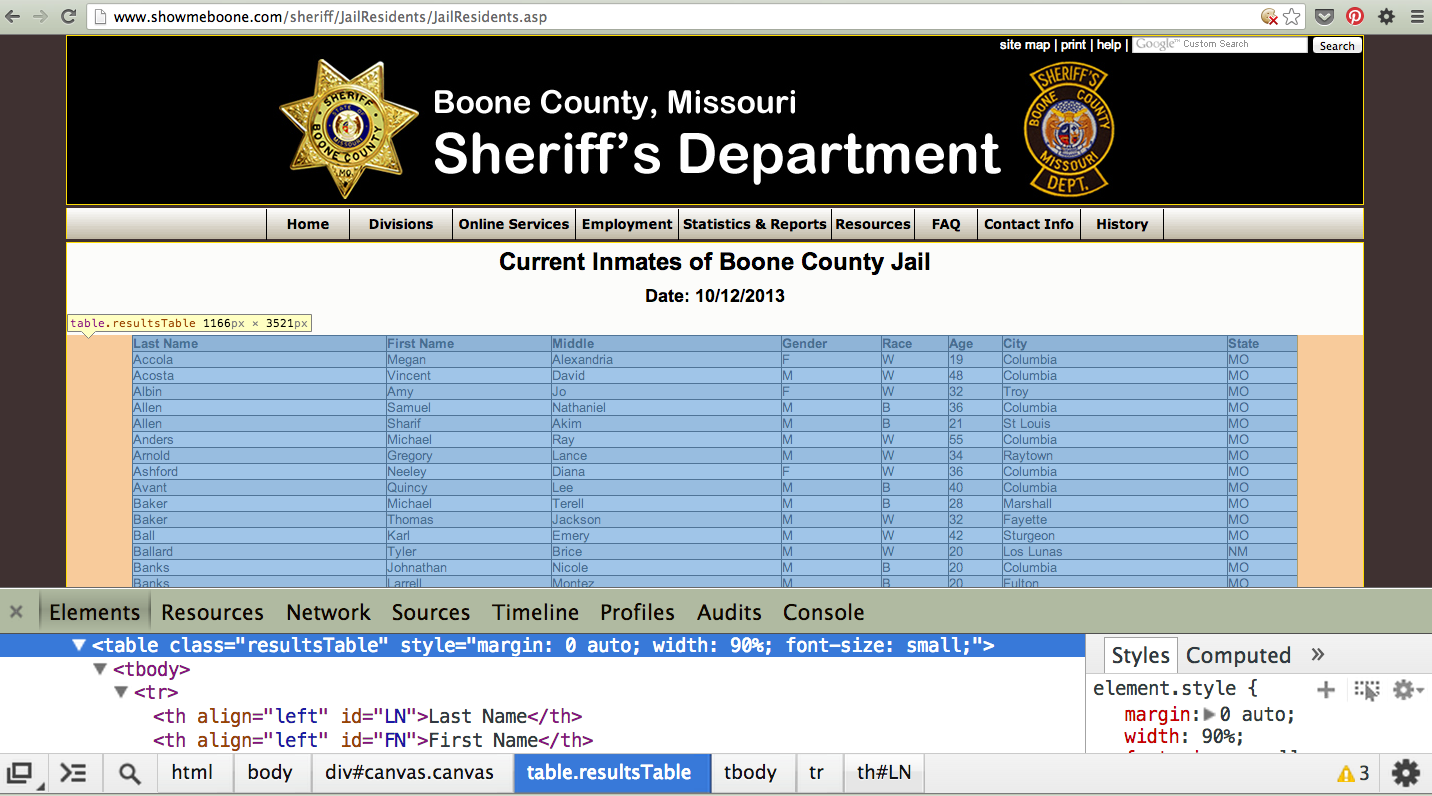

The target is a regularly updated roster of inmates at the Boone County Jail in Missouri. Boone County is home to Columbia, where you can find the University of Missouri’s main campus and the headquarters of Investigative Reporters and Editors.

You may notice that there’s an export button on this page. When this tutorial was first written, the jail did not allow you to export to a CSV – of course, if there is an export option, take it! As a simple site though, it’s still a good way to learn to scrape. Sometimes you may even find that an export doesn’t contain all of the information a site has – in that case, you may want to scrape it anyway!

Installing dependencies¶

The scraper will use Python’s BeautifulSoup toolkit to parse the site’s HTML and extract the data.

We’ll also use the Requests library to open the URL, download the HTML and pass it to BeautifulSoup.

Since they are not included in Python’s standard library, we’ll first need to install them using pip, a command-line tool that can grab open-source libraries off the web. If you don’t have it installed, you’ll need to follow the prequisite instructions for pip.

In OSX or Linux try this:

sudo pip install bs4

sudo pip install requests

On Windows give it a shot without the sudo.

pip install bs4

pip install requests

Analyzing the HTML¶

HTML is the framework that, in most cases, contains the content of a page. Other bits and pieces like CSS and JavaScript can style, reshape and add layers of interaction to a page.

But unless you’ve got something fancy on your hands, the data you’re seeking to scrape is usually somewhere within the HTML of the page and your job is to write a script in just the write way to walk through it and pull out the data. In this case, we’ll be looking to extract data from the big table that makes up the heart of the page.

By the time we’re finished, we want to have extracted that data, now encrusted in layers of HTML, into a clean spreadsheet.

In order to scrape a website, we need to understand how a typical webpage is put together.

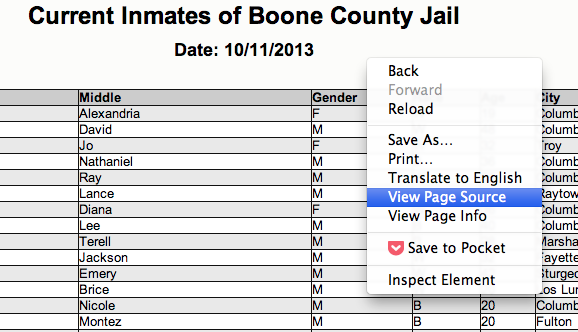

To view the HTML code that makesup this page () open up a browser and visit out target. Then right click with your mouse and select “View Source.” You can do this for any page on the web.

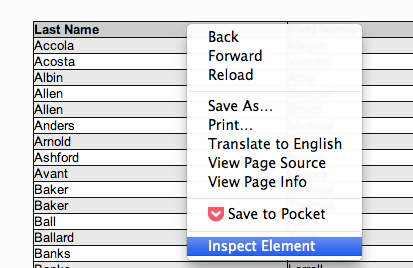

We could fish through all the code to find our data, but to dig this more easily, we can use your web browser’s inspector tool. Right click on the table of data that you are interested in and select ‘inspect element.’

Note

The inspector tool might have a slightly different name depending on which browser you’re using. To make this easy on yourself, consider using Google Chrome.

Your browser will open a special panel and highlight the portion of the page’s HTML code that you’ve just clicked on.

There are many ways to grab content from HTML, and every page you scrape data from will require a slightly different trick.

At this stage, your job is to find a pattern or identifier in the code for the elements you’d like to extract, which we will then give as instructions to our Python code.

In the best cases, you can extract content by using the id or class already assigned to the element you’d like to extract. An ‘id’ is intended to act as the unique identifer a specific item on a page. A ‘class’ is used to label a

specific type of item on a page. So, there maybe may instances of a class on a page.

On Boone County’s page, there is only table in the HTML’s body tag. The table is identified by a class.

<table class="resultsTable" style="margin: 0 auto; width: 90%; font-size: small;">

Extracting an HTML table¶

Now that we know where to find the data we’re after, it’s time to write script to pull it down and save it to a comma-delimited file.

Let’s start by creating a Python file to hold our scraper. First jump into the Code directory we made at the beginning of this lesson.

cd Code

Note

You’ll need to mkdir Code (or md Code in Windows) if you haven’t made this directory yet.

Then open your text editor and save an empty file into the directory name scrape.py and we’re ready to begin. The first step is to import the requests library and download the Boone County webpage.

import requests

url = "https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s"

response = requests.get(url, headers={"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0"})

html = response.content

print(html)

Save the file and run this script from your command line and you should see the entire HTML of the page spilled out.

python scrape.py

Next import the BeautifulSoup HTML parsing library and feed it the page.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

print(soup.prettify())

Save the file and run the script again and you should see the page’s HTML again, but in a prettier format this time. That’s a hint at the magic happening inside BeautifulSoup once it gets its hands on the page.

python scrape.py

Next we take all the detective work we did with the page’s HTML above and convert it into a simple, direct command that will instruct BeautifulSoup on how to extract only the table we’re after.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

print(table.prettify())

Save the file and run scrape.py again. This time it only prints out the table we’re after, which was selected by instructing BeautifulSoup to return only those <table> tags with resultsTable as their class attribute.

python scrape.py

Now that we have our hands on the table, we need to convert the rows in the table into a list, which we can then loop through and grab all the data out of.

BeautifulSoup gets us going by allowing us to dig down into our table and return a list of rows, which are created in HTML using <tr> tags inside the table.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

for row in table.findAll('tr'):

print(row.prettify())

Save and run the script. You’ll not see each row printed out separately as the script loops through the table.

python scrape.py

Next we can loop through each of the cells in each row by select them inside the loop. Cells are created in HTML by the <td> tag.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

for row in table.findAll('tr'):

for cell in row.findAll('td'):

print(cell.text)

Again, save and run the script. (This might seem repetitive, but it is the constant rhythm of many Python programmers.)

python scrape.py

When that prints you will notice the word “Details” appears over and over. That’s because of the link to more details at the end of each table row. To remove that, we can use the list slicing we learned earlier to return everything but the last column in each row.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

for row in table.findAll('tr'):

for cell in row.findAll('td')[:-1]:

print(cell.text)

Save and run the script. Everything should be much better.

$ python scrape.py

Now that we have found the data we want to extract, we need to structure it in a way that can be written out to a comma-delimited text file. That won’t be hard since CSVs aren’t any more than a grid of columns and rows, much like a table.

Let’s start by adding each cell in a row to a new Python list.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

for row in table.findAll('tr'):

list_of_cells = []

for cell in row.findAll('td')[:-1]:

text = cell.text

list_of_cells.append(text)

print(list_of_cells)

Save and rerun the script. Now you should see Python lists streaming by one row at a time.

python scrape.py

Those lists can now be lumped together into one big list of lists, which, when you think about it, isn’t all that different from how a spreadsheet is structured.

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

list_of_rows = []

for row in table.findAll('tr'):

list_of_cells = []

for cell in row.findAll('td')[:-1]:

text = cell.text

list_of_cells.append(text)

list_of_rows.append(list_of_cells)

print(list_of_rows)

Save and rerun the script. You should see a big bunch of data dumped out into the terminal. Look closely and you’ll see the list of lists.

python scrape.py

To write that list out to a comma-delimited file, we need to import Python’s built-in csv module at the top of the file. Then, at the botton, we will create a new file, hand it off to the csv module, and then lead on a handy tool it has called writerows to dump out our list of lists.

import csv

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

list_of_rows = []

for row in table.findAll('tr'):

list_of_cells = []

for cell in row.findAll('td')[:-1]:

text = cell.text

list_of_cells.append(text)

list_of_rows.append(list_of_cells)

outfile = open("inmates.csv", "w")

writer = csv.writer(outfile)

writer.writerows(list_of_rows)

Save and run the script. Nothing should happen – at least to appear to happen.

python scrape.py

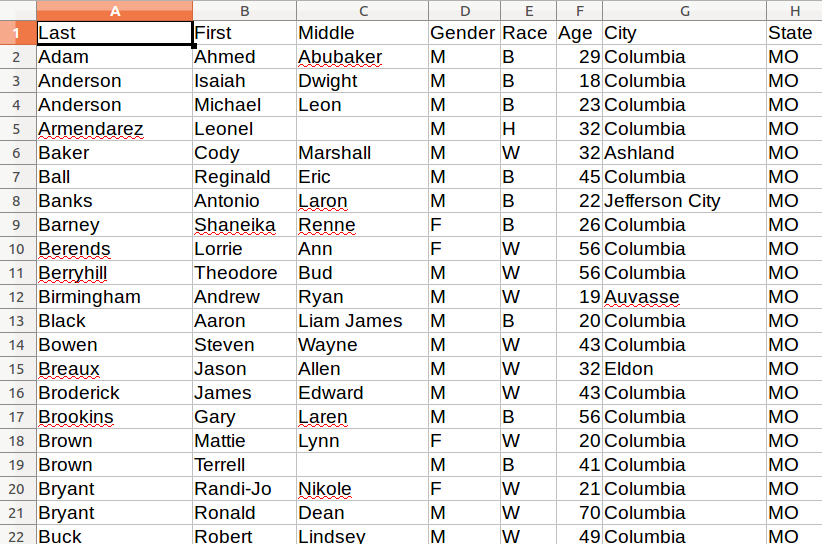

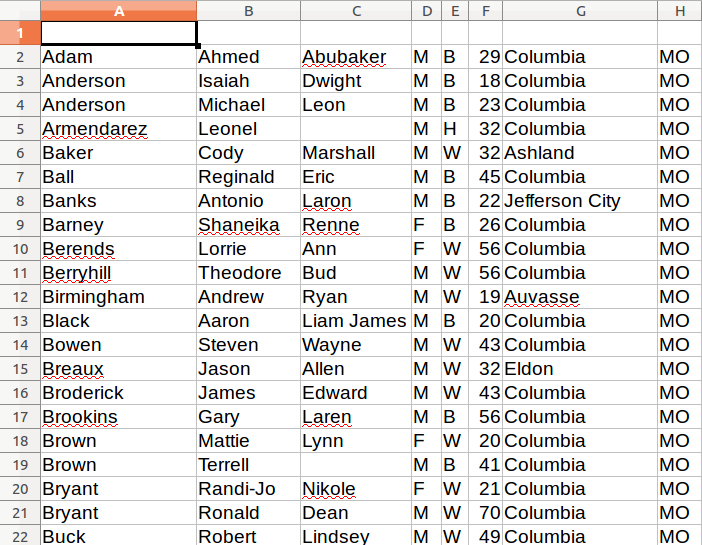

Since there are no longer any print statements in the file, the script is no longer dumping data out to your terminal. However, if you open up your code directory you should now see a new file named inmates.csv waiting for you. Open it in a text editor or Excel and you should see structured data all scraped out.

There is still one obvious problem though. There are no headers!

Here’s why. If you go back and look closely, our script is only looping through lists of <td> tags found within each row. Fun fact: Header tags in HTML tables are often wrapped in the slightly different <th> tag. Look back at the source of the Boone County page and you’ll see that’s what exactly they do.

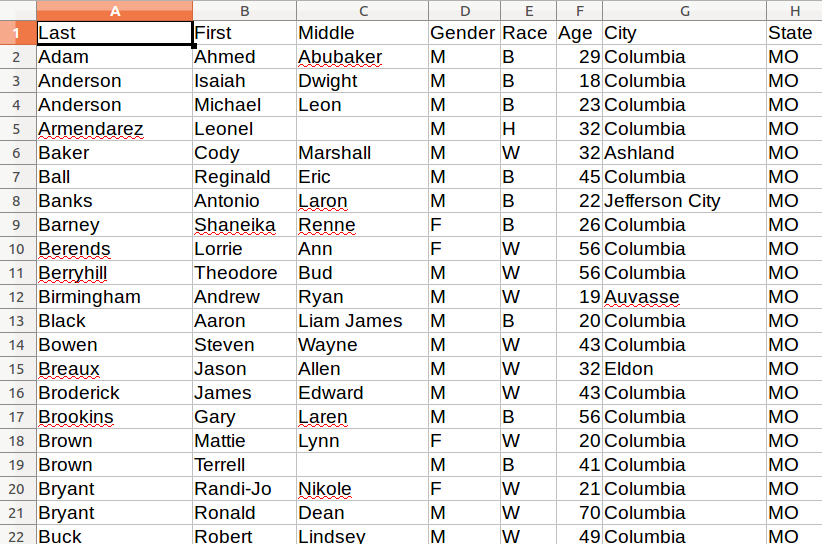

But rather than bend over backwords to dig them out of the page, let’s try something a little different. Since we know what the headers are, we can just write them out ourselves before we write the rest of the file.

import csv

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

list_of_rows = []

for row in table.findAll('tr'):

list_of_cells = []

for cell in row.findAll('td')[:-1]:

text = cell.text

list_of_cells.append(text)

list_of_rows.append(list_of_cells)

outfile = open("inmates.csv", "")

writer = csv.writer(outfile)

writer.writerow(["Last", "First", "Middle", "Suffix", "Gender", "Race", "Age", "City", "State"])

writer.writerows(list_of_rows)

Save and run the script one last time.

python scrape.py

Our headers are now there, and you’ve finished the class. Congratulations! You’re now a web scraper.

But that’s not all: Getting the missing data¶

Since this scraper was first written, the sheriff’s office changed how it displays inmates. You’ll note it now only shows 50 rows at a time, and your scraper only downloads 50 rows at a time. This is a problem – you want all of the information, not just 50 rows!

But the sheriff’s office offers a handy way to change how many rows are shown, with a default of 50.

Look at the HTML:

<span>

Page Size </span>

<input class="mrcinput" name="max_rows" size="3" title="max_rowsp" type="text" value="222" />

Here’s where it shows you the words “Page Size” as well as an input section with a variable named max_rows and a value of 50.

A handy technique: Sometimes web pages will accept input in the URL itself by passing a variable after a ?. Sometimes it works to play around with the URL and see how the site changes.

In this case, instead of scraping the main URL:

https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s

Try scraping it by passing a new value for max_rows:

https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s?max_rows=500

To implement, just change your url variable like so:

import csv

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

url = 'https://report.boonecountymo.org/mrcjava/servlet/SH01_MP.I00290s?max_rows=500'

response = requests.get(url, headers={'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0'})

html = response.content

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

table = soup.find('tbody', attrs={'class': 'stripe'})

list_of_rows = []

for row in table.findAll('tr'):

list_of_cells = []

for cell in row.findAll('td')[:-1]:

text = cell.text

list_of_cells.append(text)

list_of_rows.append(list_of_cells)

outfile = open("inmates.csv", "w")

writer = csv.writer(outfile)

writer.writerow(["Last", "First", "Middle", "Suffix", "Gender", "Race", "Age", "City", "State"])

writer.writerows(list_of_rows)

Extra Credit: How would you get the rest of the details?¶

In the class, we simply tossed out the “Details” column of data. But we only were getting the text of the cells, which was the word “Details.”

In actuality, that cell contains a link that, when we go to it, gives more information like height, weight, hair color and charge information. Some of this is available in the export, but not all of it! The HTML for the button that leads you there looks something like:

<td class="one td_left" data-th="">

<a class="_lookup btn btn-primary" height="600" href="RMS01_MP.R00040s?run=2&R001=&R002=&ID=40644&hover_redir=&width=950" linkedtype="I" mrc="returndata" target="_lookup" width="860"><i class="fa fa-large fa-fw fa-list-alt"> </i>Details</a>

</td>

Note

When you inspect the code, you might see & instead of & in the URL. & is HTML ecoding for an ampersand (the & symbol). If you’re trying to go to a URL and you see the encoded version, try replacing it with an ampersand.

Do you think that URL – the text after the “href” in the HTML above – might have some kind of clue as to how to access the further data? How would that look like within our current loop? At what point would you go back to get the extra details? The first thing I would do is